As part of a residency project at Hot Bed Press, I’ve been exploring the archives underneath Salford Museum & Art Gallery. I’m interested in faces, so I’m lucky to have a major resource like this almost next-door to the print studio. It’s catalogued online at www.artuk.org and as I looked through the collection I was struck by a number of portraits of unknown people by unknown artists.

The gallery’s Collections Manager, Peter Ogilvie, showed me the collection and pulled out the particular portraits I had spotted online – some were in fact now known to be of certain people or by certain artists. Some were actually photographs over painted with oils, a process apparently popular for a while in the 19th century which creates a peculiarly life-like image but arguably allows less room for artistic interpretation. At the end of the afternoon we had a collection of five portraits of unknown people by unknown artists.

I’m intrigued – who were they? Having a portrait made implies that somebody thought their images were worth preserving and hanging on a wall – perhaps because they were eminent, or perhaps they were just convenient sitters for artists who needed to create. Perhaps they were simply loved. Why did the sitter and the artist invest the time to do this, did they think they were creating a legacy of some kind… and how long does it take before somebody disappears? The portraits reflect the pressures of their times – what are the sitters and the arists showing of themselves and their circumstances? How much of what has been painted reflects the real person, how much reflects only the persona they are adopting – the businessman, the politician, the archetypal pretty woman?

I’ve spent some time with them and slowly aspects of what may or may not be their true characters are starting to emerge – quite literally, emerging from the wood as I begin on some blocks. There’s probably over a hundred years between the earliest portrait and the latest – and we see not only the person, but the fashions of the day, not just in terms of what they are wearing but also in the way they are depicted. The life experience of their particular time must also have some bearing.

I’m stripping away the trappings, removing collars, hairstyles, and making woodcuts that are roughly life-size. This immediately makes them more equal as a group, as we can no longer judge anything from their clothing or their pose.

Taking away the visual clues that these people are from before our time seems to make them more available to us in the present – they might be Salford residents, people who are not out of place today. Yet there is still something slightly ghostly about the way they are appearing, emerging from the woodwork, pale faces against the darkness. Their expressions are accusatory, knowing, seductive. Am I allowing their essence to emerge from the wood grain, or am I, perhaps inevitably, putting my own time on them?

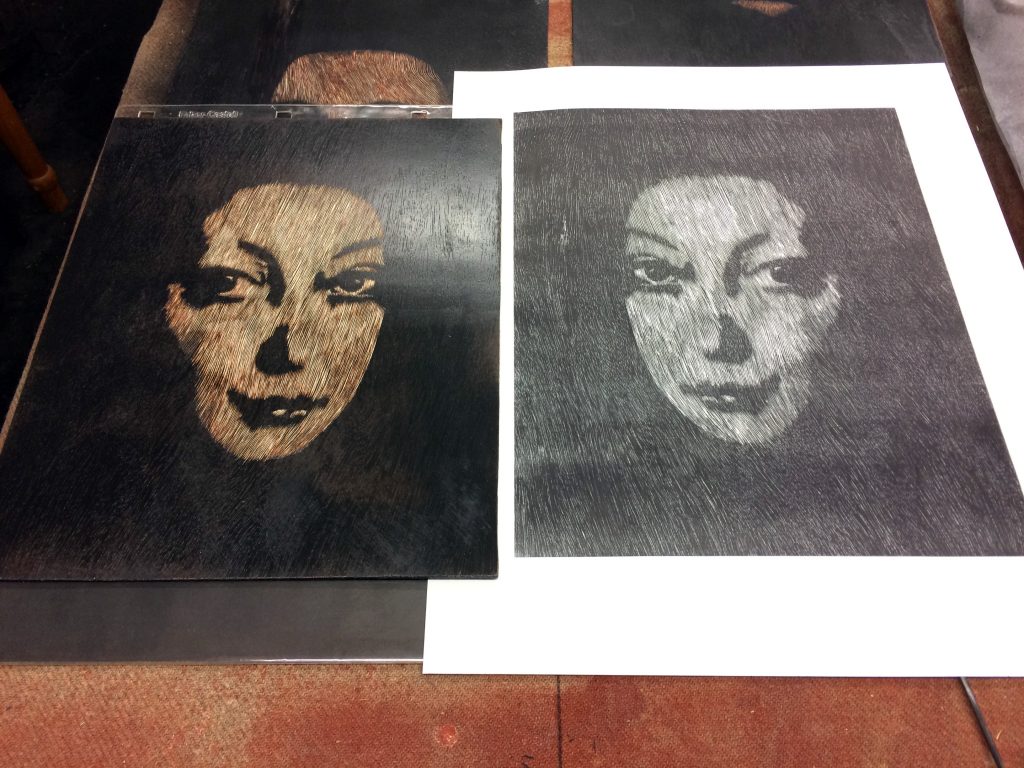

The wood I’m using has two colours when cut – a reddish brown that follows the contours of my cuts, and almost white where the cuts are deep and the layers of wood are fully cut away. These contrast sharply with a surface coating of black. I like the suggestion of different depths, layers, something underneath.

Curiously, the colours in the blocks make them seem more alive than my first black-and-white proof prints.

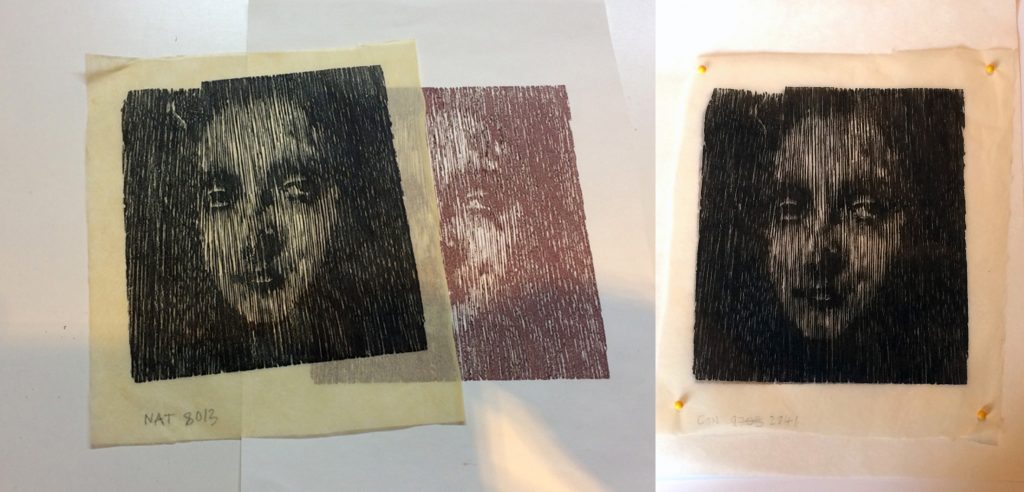

This makes me want to find a way to achieve a print with more depth. How do you express the depth of a person, their experience and their life, in print? I’m experimenting with overlay of the same small test block using different colours and thicknesses of paper, and different colours of ink. I like the version with the top later simply pinned over another coloured impression underneath – it draws attention to the surface that is visible and raises the question of what’s behind it.